CNN: Meet 5 young entrepreneurs who are making the world a better place

Ending hunger, employing refugees, and lighting remote islands: these are just some of the big issues that these five young social entrepreneurs are tackling in their countries, as featured in the Forbes’ 30 Under 30 Summit in Asia 2017, held in Manila. From left: Ankhit Kawatra of Feeding India, Daroath Phav of WaterSHED, Matthew Cua of SkyEye, Aisa Mijeno of SALt, and Nirary Dacho of Refugee Talent. Photos by KITKAT PAJARO

Read the article in CNN Philippines.

Manila (CNN Philippines Life) — Early into the Forbes 30 Under 30 Summit Asia 2017, the crowd cheered on as two very young CEOs — Sanjay Kumaran, 15 years old, and Shravan Kumaran, 17 — talked about how their dad didn’t want to shell out money for a VR (virtual reality) unit they wanted to test for one of their ventures. The problem is, VR headsets in the market are priced at Rs 26,000 to 40,000 (around ₱20,000 to ₱30,000) so their dad, an associate vice president at a technical solutions company, refused. The brothers solved the problem by creating their own VR headset, GoVR, which is significantly lower-priced than the usual VR headset.

The brothers released their first app, Catch Me Cop (a mobile game where you play a con evading a nationwide hunt) when the youngest of them was only 11 years old. They learned how to code nine years ago by reading a lot of coding books.

Since then, they’ve dispatched various apps such as Alphabets Board, which aims to help kids learn the alphabet faster, and Prayer Planet, “an app to pray [to] God easily and quickly on your mobile device.” They’ve accumulated 70,000+ downloads in 60 countries and was hailed by Apple as the youngest mobile application programmers in India.

Sanjay Kumaran and Shravan Kumaran of GoDimensions released their first gaming app, CatchMeCop, when the younger of the brothers was 11 years old. Photo by KITKAT PAJARO

Forbes’s recent 30 Under 30 Summit Asia, held in Manila, is a smattering of young folks hailed by the magazine as “young leaders in 10 industries who are rising stars in the Asia-Pacific Region” — names their industries will be talking about years from now.

Though the list spans entertainment, arts, and marketing, to manufacturing and retail, list editor Rana Wehbe of Forbes Asia noted that social entrepreneurs are dominant on the list, responding to the issues of the Asia-Pacific region in more specific ways.

“There’s a lot of young people rising up to the challenge and taking on big problems — hunger in India, refugees in Australia,” says Wehbe. “They’re building social enterprises that are sustainable or on their way to be sustainable to make sure that even after they’re gone, [they’re] going to still be solving problems. It doesn’t depend on one person being charitable and giving money. Money’s gonna run out at one point.”

Rana Wehbe, the senior digital editor of Forbes Asia, put together the 30 Under 30 Asia List. She says: “There are a lot of people with great ideas out there. The ones that end up maybe failing sometimes to get their vision out there are the game changers, the first ones that do something and the rest will kind of jump on the bandwagon.” Photo by KITKAT PAJARO

Wehbe is quick to point out that unlike all the other Forbes lists, the 30 Under 30 list is not about wealth but rather success, focusing on social good, innovation, and impact. The summit brings together over 250 participants and is an opportunity to exchange ideas with their peers and present concepts and potential solutions.

Here are five of the youngest innovators and game-changers from the summit who are addressing some of the world’s most pressing problems — from climate change to hunger.

Aisa Mijeno invented a lamp that runs on salt water. She aims to light up coastal and other remote communities in the Philippines using her saltwater lamps. Photo by KITKAT PAJARO

AISA MIJENO, Co-founder and CEO of SALt (Philippines)

For Mijeno, a scientist who invented a salt water-powered lamp for remote and coastal communities, sharing the spotlight with former U.S. president Barack Obama and Alibaba CEO Jack Ma during the APEC CEO Summit 2015 was a double-edged sword. On one hand, it opened doors for them to work with NGOs and corporations who might want to sponsor SALt for communities’ lamps; but on the other hand, people expected a speedy manufacturing process for mass production of the lamps.

“It’s hard to get something out in the market, especially electronics,” says Mijeno. “We need to make sure [that] all the claims that we have when we were submitting a patent are met.”

For the project, Mijeno and her team want to go to specific areas in the countries which were left out of the national power grid, and by charitable companies that only helped bigger communities so as to maximize impact.

“We want to help the outskirts, fill in the gaps, especially in the island communities in the Philippines,” says Mijeno. “The communities we’re trying to support are not huge communities eh […] and those are communities with less than 500 households kasi sila ‘yung usually naiiwan, especially [by] local government and NGOs dahil [these organizations] want to maximize their support. Logistics and distribution may gastos ‘yan eh, so they choose communities with more than 500 households. Paano naman ‘yung communities na 80 households lang?”

SALt works with these communities from the ground up, making sure their needs are met and [that] a sustainable plan is in place.

“Although charity helps, its not the way to do things,” she says. “Kapag charity, after ibigay mo, mawawala after some time, so you have to continuously provide people with basic needs kasi hindi ikaw yung tutulong sa kanila. You have to enable an environment [for them] to help themselves, alleviate themselves from poverty. All of us have to work hand in hand.”

Matthew Cua’s SkyEye has helped government agencies, NGOs, and private companies use drones and unmanned aerial vehicles for disaster response, aerial surveys, and mapping projects. Photo by KITKAT PAJARO

MATTHEW CUA, Founder, SkyEye Analytics (Philippines)

SkyEye started as an offshoot of a master’s degree requirement for Cua and his fellow students in 2009. Cua was interested in tackling climate change, but at that time, satellite images were expensive and hard to obtain. So they created their own drones for their surveys and research.

One of their earliest and biggest commissions was when they were deployed to survey the areas affected by typhoon Yolanda in 2013.

“It made us realize the response was not coordinated in any way,” recounts Cua of their experience. “We were spending resources inefficiently, therefore we had clogging in the ports, in the airport of Tacloban, aid was delivered in some places but not other places … Tacloban City had so much aid but the cities around Tacloban didn’t have any aid, it’s all inefficient.”

Since then, SkyEye has worked with various private companies, government agencies, and NGOs such as the United Nations OCHA (Office for Coordination of Human Affairs) for disaster response, mapping projects, aerial surveys, and other imaging and data-driven programs.

SkyEye customizes their drones, since there are certain factors in the country that can hamper their operations.

“We have high humidity and the risk of flying drones is higher. Unlike in other countries, the weather [here] can change dramatically,” says Cua. “One hour it’s raining hard and suddenly, it’s sunny, and then rainy again. So we have to be flexible in how we use drones. If something hits our drone, we can change and repair the system so it can fly again.”

Now that Cua is at the forefront of gathering images of the country’s landscape, he’s also witness to the different changes brought about by climate change.

“I’m a climate change scientist initially,” he says. “You’ll see a lot of changes over time in our environment due to climate change. For example, coastal erosion, kaingin, we are able to see firsthand the impact of climate change, waste — we work with seven lakes in Laguna on fish kills — we see uncontrolled development, which increase the risk of the area, there are villages in areas where villages should not be built. We see a lot of these things and we hope that the images that we provide help decision makers in making decisions.”

Daroath Phav of WaterSHED helps the rural poor of Cambodia invest on latrines for their health and comfort. Photo by KITKAT PAJARO

DAROATH PHAV, Executive Director, WaterSHED (Cambodia)

In 2010, more than 75 percent of the rural poor in Cambodia did not have toilets and still passed waste in the open. WaterSHED executive director Daroath Phav explains this has been the way for these people, from their ancestors up to now, as an established communal behavior.

“That’s one of the challenges, changing the people’s behavior. [People have been doing this for a long time] so they say ‘I’m okay. So why do I need one?’” says Phav. He joined WaterSHED in 2011 and helped rural families to invest in latrines and see the importance of having their own toilet.

“We don’t [just] say [a] toilet is good, [we tell them a] toilet is good for comfortability,” says Phav. “Getting a toilet is safety, comfortability, owning a toilet can be a prize for a family. This is the message we send to the rural poor people.”

Convincing the families to invest in their health is one issue, but it is also another issue to supply this demand. This means Phav, who has a business background, also had to create a rural market to address this need. He likens it to buying a smartphone.

“If you want people to buy an iPhone, you want to have an online store where people can buy easily,” says Phav. “So the idea that we have is like that, make it easy for people to buy it.”

“There are places that are really remote that you can’t just buy a toilet easily,” he continues. “Our job is to create a supplier and [make] the design that people want. When you’re a charity you don’t think ‘Oh, is this a design that the customer wants?’ To us, we need to look at it.”

WaterSHED has had success in selling 150,000 toilets across Cambodia, generating $6 million for local businesses and increasing the sanitation coverage from 25 to 50 percent in just five years.

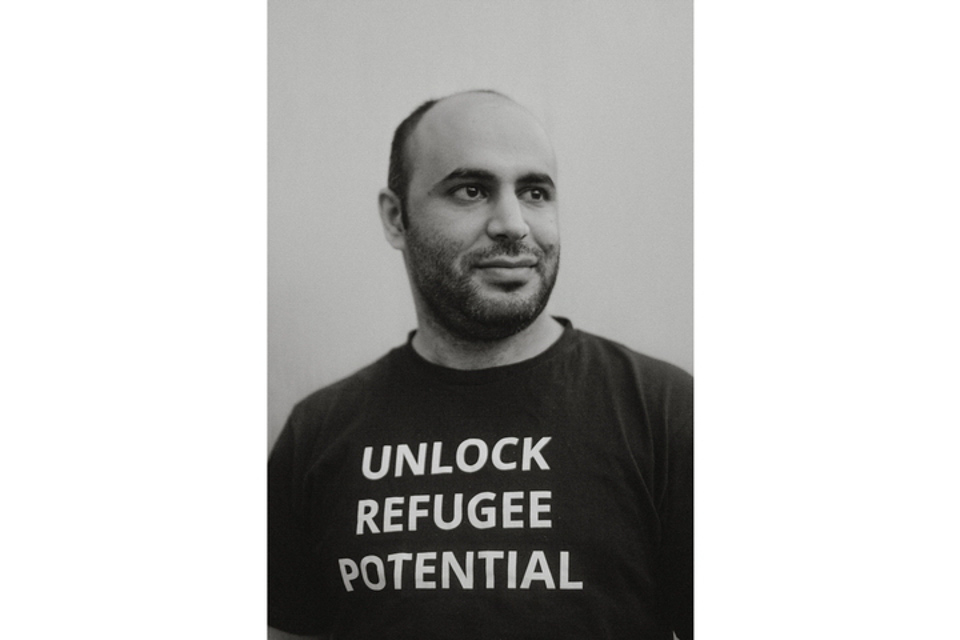

Nirary Dacho of Refugee Talent helps his fellow refugees and migrants in Australia get employment. Photo by KITKAT PAJARO

NIRARY DACHO, Co-founder, Refugee Talent (Australia)

Dacho was a refugee from Syria and was in dire straits because he couldn’t find a job placement. Despite the fact that he has a master’s degree in web science, with more than eight years of experience as an IT analyst and could speak English, it was still difficult for him to find a job in Australia. Working in Australia meant you have to have local experience, which Dacho didn’t have. But it took an appearance in a news segment as an unemployed refugee before offers came and eventually, employment.

Now, Dacho has co-founded Refugee Talent with Anna Robson, who used to work at a detention center. The company helps refugees and migrants to get job placements by improving their resume, preparing them for interviews, evaluating their English level, and fixing their profile. They also set up mixers and networking opportunities for their clients and the candidates.

“[We gain the trust of the employers] when we have success stories and testimonies from the businesses,” says Dacho. “They realize how much there is an untapped talent in refugees and migrant communities. With more success stories, people start trusting us, they realize how much these people are skilled, educated, and hard workers who just want to [practice] their profession.”

Dacho remembers Refugee Talent’s first successful placement, a woman from Syria who has an accounting background. They were able to secure her a job at a travel agency. And after only a few months, they were already training her as CFO “because she was very smart, efficient, and highly experienced.”

They’ve been responding to Australia’s shortage of IT developers, bookkeepers, accountants, and laborers. And in just over a year, Refugee Talent has broken barriers for the people that they are able to help.

Says Dacho, “[The employers] realize that even those people don’t have local experience, but they have high experience overseas and their qualifications — even though its overseas that doesn’t mean it doesn’t have any value, they can do that job better than anyone else.”

Ankhit Kawatra of Feeding India gets food donations excess from weddings, cafeterias, and other events, and donates them to those in need in India. Photo by KITKAT PAJARO

ANKHIT KAWATRA, Founder, Feeding India (India)

It was an astonishing waste of food — for 10,000 people at a celebrity wedding — that finally made up Kawatra’s mind to address the hunger problem in India.

“Everybody, at some point in their life, they go to a wedding,” says Kawatra. “[They’d ask] what would happen to all the food in a wedding — all of it, not just in that [one] wedding, but throughout the country — was going to go to the bin. How can you live in a country where we know poverty exists but not be able to solve it?”

Kawatra then left his cushy corporate job to establish Feeding India, which takes excess food from events, weddings, cafeterias, and other places to distribute them to those who need it.

“In order to combat that issue, it’s important to spread awareness. So the first thing I did was get a lot of volunteers, they would collect the food.”

Feeding India has a system in place. They have 7,000 volunteers in 50 cities ready to get and distribute food. To make sure that the quality of food is still at 100 percent, Kawatra has consulted restaurateurs and chefs to make a quality check criteria. The team tastes the food themselves so they personally know if it still can be eaten or not. They have refrigerated vans in place, on call 24/7, ready to pick up and deploy food.

Kawatra makes sure that the places in India that have excess food and the places that need food are connected, hence Feeding India’s “hyperlocal” approach.

“India has 200 million undernourished people,” he says. “That’s unimaginable. Two hundred million people don’t have food but we have the best technologies. We have everything. I thought to build awareness and make sure everyone in a colony, everyone, needs to be engaged. It needs to be a hyperlocal model, rather than a model enforced on others.”

Feeding India has since served 4.8 million meals in the three years since it was founded. Kawatra has also gained recognition for his efforts, including a Young Leaders Award from Queen Elizabeth II.