Die WELT: My house, my moped, my toilets | How a businesswoman turns toilets into a luxury items

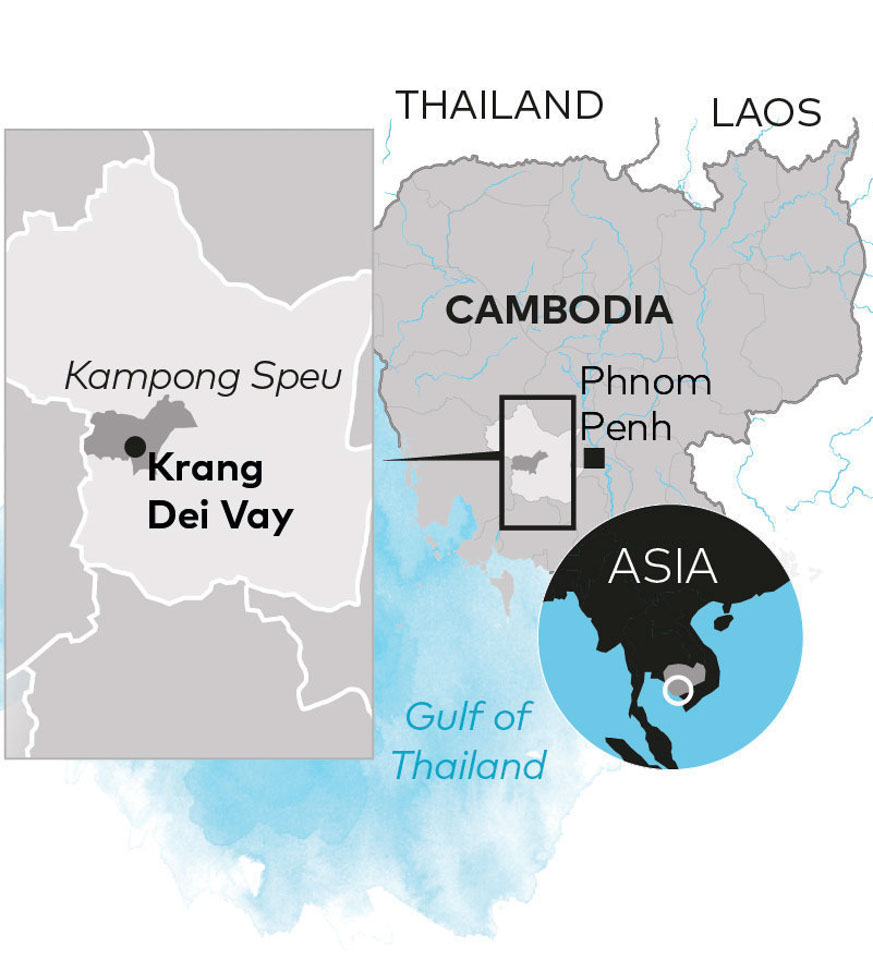

A toilet saleswoman points to a poster showing man’s best friend and a man relieving themselves outdoors, and says: “They do it like dogs. The dog can’t choose to do it differently but you can – by buying a toilet!” In Kampong Speu province, two hours east of the Cambodian capital Phnom Penh, 20 people listen to the businesswoman’s pitch. Some of them look shame-faced at the ground. They do their business in the field behind their homes – just like 53 percent of Cambodians.

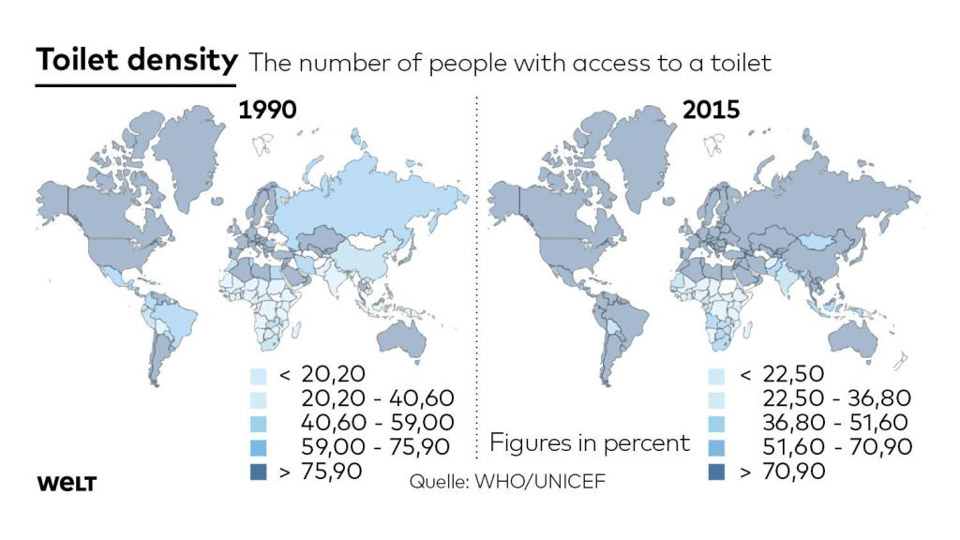

But going to the toilet outdoors is a health risk. It causes faeces to enter the groundwater and then the food chain. Poor hygiene conditions are the main cause of infectious diseases – and many child deaths. Yet few people are aware of this in Cambodia, which has the lowest toilet density in Southeast Asia.

The government has set itself an ambitious target. It wants everyone to have access to a toilet facility by 2025 – and it is turning to western marketing strategies to achieve that aim. Its Cambodian slogan translates as something like: “My House, My Moped, My Toilet”. The government wants toilets to be seen as luxury items that make Cambodians proud, like Porsches that people admire in the street.

A toilet costs 180 to 450 euros

To Channy Hun, her toilet outhouse made of stone is like a dream car. It was completed five days ago then plastered, painted sky-blue and given a final aesthetic flourish with a red door. It’s a feast for the eyes. By contrast, the 23-year-old’s home is a simple wooden construction with dried palm leaves for a roof. Every villager knows that Channy Hun is the young woman with the blue toilet outhouse. She’s the woman who speaks up proudly when the issue of toilets is raised in community meetings.

Channy Hun in front of her new, 500-dollar toilet

“I’m very happy that I no longer have to go into the forest. Finally, no more mosquito bites!” Channy Hun laughs and strokes her belly tenderly as she speaks, adding: “It will also make life easier for me and the baby.” Her pregnancy was the deciding argument for getting the luxury of a toilet. She and her sisters had previously spent three years discussing it with their mother in vain.

Toilets come at a price: 180 to 450 euros apiece, which is a lot in a country with an annual per capita income of around 900 euros. “Too expensive” is therefore the most common reason given for non-existent toilet facilities. However, each buyer has the option of taking out a micro-loan and buying a toilet in installments, making the cost just over two euros per month.

“Many people don’t see the need”

“Money is just an excuse,” says Geoff Revell of the non-governmental organisation (NGO) Watershed Asia in Phnom Penh. He thinks the problem is a psychological one. “Even if people have the money, they wouldn’t buy a toilet because they don’t see it as an attractive product,” he explains. Other purchases have priority. For example, 94 percent of Cambodians have a smartphone and one in five inhabitants are registered as having a motorbike or car that is generally used by the whole family. “Many people don’t see the need for toilets. They think relieving themselves outdoors is normal because that’s how it’s been done for generations,” is how Revell explains the local attitude.

According to a World Bank study, each rural Cambodian family loses 70 US-dollars annually as a result of illness-related losses caused by poor sanitary conditions. Investing in a toilet does pay off, but communicating that fact to local people is a challenge. Raising health concerns does not help.

This is how a typical toilet outhouse inThis is how a typical toilet outhouse in Cambodia looks – with a bowl of water to flush it Cambodia looks – with a bowl of water to flush it

“People don’t quit smoking either, even though they know it’s bad for their health,” says the Watershed director. That’s the reason why organisations focus on emotions and use a simple, human approach to sales. For example, colour and appearance play a big role – as does social pressure. Once one family in the village has a toilet, the neighbours quickly follow suit.

“Women have better sales skills”

Sambeth Bo is inspecting a toilet construction site. She’s an expert at it because toilets are her livelihood. Two men are busy laying bricks. Meanwhile, work has already been completed on a three-metre deep hole stabilised with concrete rings. Sewage will eventually flow into this hole from the adjacent toilet building because there is no sewerage system. The workers install a simple squatting toilet in the ground. A large bowl of water with which to ‘flush’ the toilet completes the outhouse’s interior.

Bo’s business has boomed since the 33-year-old started selling toilets nearly a year ago. A Watershed programme taught her how to build a supply network for bricks, tiles and toilet pans,as well as how to cast the concrete rings for sewage outlets herself. It’s all she needs for her business. Bo has sold 194 sanitary facilities within 11 months, thereby doubling the number of households with toilets in her municipality from 11 to 23 percent. She is proud of her achievement.

Sambath Bo inspects the toilet construction in Krang Dei Vay village

It is uncommon for women in rural Cambodia to own a business. Yet Watershed is mainly focusing its efforts on women for one simple reason: “Women have better sales skills than men,” says Geoff Revell. They also know how best to talk to mothers, who are the NGO’s main target group since they look after children and are therefore receptive to health appeals.

What’s more, it is predominantly women who suffer the inconveniences associated with the lack of toilets. They often feel shamed into waiting the whole day to relieve themselves, only finally doing so once darkness falls. It is not unusual for women to fall victim to sexual assaults when they do venture into the fields or forests. A toilet means privacy and safety – and therefore improved quality of life.

There was no infrastructure for construction

Sambath Bo greets the customer whose toilet construction site she has just inspected. Lina Chouch, 18, clutches her 30-day-old baby to her breast. “I’m really looking forward to the toilet because I’m used to it from my parents’ house,” she says, adding that she stayed with her parents during her pregnancy for that reason. Lina Chouch moved in with her husband after the birth – and the discussions started: “I told my husband I don’t like going into the field and I wanted to have a toilet. He said he didn’t know how to build one.” That is less of an excuse than an actual problem. Many people do not know whom to turn to. Sambath Bo is set to change that in her municipality. She is the saleswoman, service provider and problem solver who both takes charge when a toilet is blocked – and organises micro-loans. Her service is available for an unlimited period of time, providing a lifelong guarantee. Building trust is her top priority.

Lina Chouch and her baby in Krang Dei Vay village

Aid organisations failed on that front for many years. They distributed toilets free of charge, but mostly just the individual parts. Somewhere in Lina Chouch’s garden lies a barely visible toilet pan overgrown with grass. “People left it there five years ago. My husband’s family didn’t know what they were meant to do with it,” she says. Such help is well intentioned but badly implemented given that Cambodia lacks the necessary infrastructure for construction and maintenance. Where toilets were concerned, service provision was long forgotten.

Free distribution by other NGOs initially made Watershed’s work difficult. The authorities laughed at Watershed’s staff when they outlined plans to sell toilets for large sums of money. After all, the donated toilets hadn’t been used. But the more than 130,000 toilet facilities that Watershed has sold since 2010 are testament to its strategy.

Toilets sell particularly well during the dry season. This period is also wedding season when couples want to offer their guests something special. It would be embarrassing if mothers-in-law had to relieve themselves in the fields wearing their best party shoes. Awareness is also growing because increasing numbers of people work in factories with toilets. They want to enjoy the same luxury at home.

Lina Chouch’s husband only gave in when a toilet building was constructed in his neighbours’ garden. Seeing the product convinced him more than his wife’s words could. But she doesn’t care. In two days’ time she will be able eto use her own toilet. Finally.

Text and Photos: Mareike Kürschner

Graphics: Jörn Baumgarten, Thomas Lees

Translation: Louise Andersen